Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021 Abridged for Primary Care Providers

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes is updated and published annually in a supplement to the January issue of Diabetes Care. The Standards are developed by the ADA’s multidisciplinary Professional Practice Committee, which comprises physicians, diabetes educators, and other expert diabetes health care professionals. The Standards include the most current evidence-based recommendations for diagnosing and treating adults and children with all forms of diabetes. ADA’s grading system uses A, B, C, or E to show the evidence level that supports each recommendation.

- A—Clear evidence from well-conducted, generalizable randomized controlled trials that are adequately powered

- B—Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies

- C—Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studies

- E—Expert consensus or clinical experience

This is an abridged version of the current Standards containing the evidence-based recommendations most pertinent to primary care. The recommendations tables and figures included here retain the same numbering used in the full Standards and so are not numbered sequentially. All of the recommendations included here are substantively the same as in the full Standards. The abridged version does not include references. The complete 2021 Standards of Care, including all supporting references, is available at professional.diabetes.org/standards.

1. Improving Care and Promoting Health in Populations

Diabetes and Population Health

Clinical practice recommendations can improve health across populations; however, for optimal outcomes, diabetes care must also be individualized for each patient. Thus, efforts to improve population health will require a combination of policy-level, system-level, and patient-level approaches. Patient-centered care is defined as care that considers individual patient comorbidities and prognoses; is respectful of and responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values; and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions. Further, social determinants of health (SDOH)—often out of direct control of the individual and potentially representing lifelong risk—contribute to medical and psychosocial outcomes and must be addressed to improve all health outcomes.

Recommendations

- 1.2 Align approaches to diabetes management with the Chronic Care Model (CCM). This model emphasizes person-centered team care, integrated long-term treatment approaches to diabetes and comorbidities, and ongoing collaborative communication and goal setting between all team members. A

- 1.3 Care systems should facilitate team-based care and utilization of patient registries, decision support tools, and community involvement to meet patient needs. B

- 1.4 Assess diabetes health care maintenance (see Table 4.1 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care) using reliable and relevant data metrics to improve processes of care and health outcomes, with attention to care costs. B

Six Core Elements

The CCM includes six core elements to optimize the care of patients with chronic disease:

- 1. Delivery system design (moving from a reactive to a proactive care delivery system where planned visits are coordinated through a team-based approach)

- 2. Self-management support

- 3. Decision support (basing care on evidence-based, effective care guidelines)

- 4. Clinical information systems (using registries that can provide patient-specific and population-based support to the care team)

- 5. Community resources and policies (identifying or developing resources to support healthy lifestyles)

- 6. Health systems (to create a quality-oriented culture)

Strategies for System-Level Improvement

Care Teams

Collaborative, multidisciplinary teams are best suited to provide care for people with chronic conditions such as diabetes and to facilitate patients’ self-management. The care team should avoid therapeutic inertia and prioritize timely and appropriate intensification of lifestyle and/or pharmacologic therapy for patients who have not achieved the recommended metabolic targets.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine is a growing field that may increase access to care for patients with diabetes. Increasingly, evidence suggests that various telemedicine modalities may be effective at reducing A1C in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with usual care or in addition to usual care.

Behaviors and Well-Being

Successful diabetes care also requires a systematic approach to supporting patients’ behavior-change efforts, including high-quality diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES).

Tailoring Treatment for Social Context

Recommendations

- 1.5 Assess food insecurity, housing insecurity/homelessness, financial barriers, and social capital/social community support and apply that information to treatment decisions. A

- 1.6 Refer patients to local community resources when available. B

- 1.7 Provide patients with self-management support from lay health coaches, navigators, or community health workers when available. A

Health inequities related to diabetes and its complications are well documented and have been associated with greater risk for diabetes, higher population prevalence, and poorer diabetes outcomes. SDOH are defined as the economic, environmental, political, and social conditions in which people live and are responsible for a major part of health inequality worldwide.

2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes

Classification

Diabetes can be classified into the following general categories:

- 1. Type 1 diabetes (due to autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency, including latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood)

- 2. Type 2 diabetes (due to a progressive loss of β-cell insulin secretion frequently on the background of insulin resistance)

- 3. Specific types of diabetes due to other causes, e.g., monogenic diabetes syndromes (such as neonatal diabetes and maturity-onset diabetes of the young), diseases of the exocrine pancreas (such as cystic fibrosis and pancreatitis), and drug- or chemical-induced diabetes (such as with glucocorticoid use, in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, or after organ transplantation)

- 4. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM; diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that was not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation)

It is important for providers to realize that classification of diabetes type is not always straightforward at presentation, and misdiagnosis may occur. Children with type 1 diabetes typically present with polyuria/polydipsia, and approximately one-third present with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Adults with type 1 diabetes may not present with classic symptoms and may have a temporary remission from the need for insulin. The diagnosis may become more obvious over time and should be reevaluated if there is concern.

Screening and Diagnostic Tests for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes

The diagnostic criteria for diabetes and prediabetes are shown in Table 2.2/2.5. Screening criteria are listed in Table 2.3.

TABLE 2.2/2.5

Criteria for the Screening and Diagnosis of Prediabetes and Diabetes

| . | Prediabetes . | Diabetes . |

| A1C | 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol)* | ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol)† |

| Fasting plasma glucose | 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L)* | ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L)† |

| 2-hour plasma glucose during 75-g OGTT | 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)* | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)† |

| Random plasma glucose | — | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)‡ |

| . | Prediabetes . | Diabetes . |

| A1C | 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol)* | ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol)† |

| Fasting plasma glucose | 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L)* | ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L)† |

| 2-hour plasma glucose during 75-g OGTT | 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)* | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)† |

| Random plasma glucose | — | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)‡ |

Adapted from Tables 2.2 and 2.5 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care. *For all three tests, risk is continuous, extending below the lower limit of the range and becoming disproportionately greater at the higher end of the range. †In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, diagnosis requires two abnormal test results from the same sample or in two separate samples ‡Only diagnostic in a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis. OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Criteria for Testing for Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Adults

| 1. Testing should be considered in adults with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m 2 or ≥23 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) who have one or more of the following risk factors: |

| • First-degree relative with diabetes |

| • High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander) |

| • History of CVD |

| • Hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension) |

| • HDL cholesterol level 250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L) |

| • Women with polycystic ovary syndrome |

| • Physical inactivity |

| • Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans) |

| 2. Patients with prediabetes (A1C ≥5.7% [39 mmol/mol], impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose) should be tested yearly. |

| 3. Women who were diagnosed with GDM should have lifelong testing at least every 3 years. |

| 4. For all other patients, testing should begin at age 45 years. |

| 5. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status. |

| 6. HIV |

| 1. Testing should be considered in adults with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m 2 or ≥23 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) who have one or more of the following risk factors: |

| • First-degree relative with diabetes |

| • High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander) |

| • History of CVD |

| • Hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension) |

| • HDL cholesterol level 250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L) |

| • Women with polycystic ovary syndrome |

| • Physical inactivity |

| • Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans) |

| 2. Patients with prediabetes (A1C ≥5.7% [39 mmol/mol], impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose) should be tested yearly. |

| 3. Women who were diagnosed with GDM should have lifelong testing at least every 3 years. |

| 4. For all other patients, testing should begin at age 45 years. |

| 5. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status. |

| 6. HIV |

Recommendations

- 2.6 Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes with an informal assessment of risk factors or validated tools should be considered in asymptomatic adults. B

- 2.7 Testing for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic people should be considered in adults of any age with overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m 2 or 23–27.4 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m 2 or ≥27.5 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) and who have one or more additional risk factors for diabetes (Table 2.3). B

- 2.8 Testing for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes should be considered in women with overweight or obesity planning pregnancy and/or who have one or more additional risk factors for diabetes (Table 2.3). C

- 2.9 For all people, testing should begin at age 45 years. B

- 2.10 If tests are normal, repeat testing carried out at a minimum of 3-year intervals is reasonable, sooner with symptoms. C

- 2.13 Risk-based screening for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes should be considered after the onset of puberty or after 10 years of age, whichever occurs earlier, in children and adolescents with overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile) or obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile) and who have additional risk factors for diabetes. (See Table 2.4 for evidence grading of risk factors.) B

Risk-Based Screening for Type 2 Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Children and Adolescents in a Clinical Setting

| . |

| Testing should be considered in youth* who have overweight (≥85th percentile) or obesity (≥95th percentile) A and who have one or more additional risk factors based on the strength of their association with diabetes: |

| • Maternal history of diabetes or GDM during the child’s gestation A |

| • Family history of type 2 diabetes in first- or second-degree relative A |

| • Race/ethnicity (Native American, African American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander) A |

| • Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, or small-for-gestational-age birth weight) B |

| . |

| Testing should be considered in youth* who have overweight (≥85th percentile) or obesity (≥95th percentile) A and who have one or more additional risk factors based on the strength of their association with diabetes: |

| • Maternal history of diabetes or GDM during the child’s gestation A |

| • Family history of type 2 diabetes in first- or second-degree relative A |

| • Race/ethnicity (Native American, African American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander) A |

| • Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, or small-for-gestational-age birth weight) B |

After the onset of puberty or after 10 years of age, whichever occurs earlier. If tests are normal, repeat testing at a minimum of 3-year intervals (or more frequently if BMI is increasing or risk factor profile deteriorating) is recommended. Reports of type 2 diabetes before age 10 years exist, and this can be considered with numerous risk factors.

An assessment tool such as the ADA risk test (diabetes.org/socrisktest) is recommended to guide providers on whether performing a diagnostic test for prediabetes or previously undiagnosed type 2 diabetes is appropriate.

Marked discrepancies between measured A1C and plasma glucose levels should prompt consideration that the A1C assay may not be reliable for that individual, and one should consider using an A1C assay without interference or plasma blood glucose criteria for diagnosis. (An updated list of A1C assays with interferences is available at ngsp.org/interf.asp.) Unless there is a clear clinical diagnosis based on overt signs of hyperglycemia, diagnosis requires two abnormal test results from the same sample or in two separate test samples. If using two separate test samples, it is recommended that the second test, which may either be a repeat of the initial test or a different test, be performed without delay. If the patient has a test result near the margins of the diagnostic threshold, the provider should follow the patient closely and repeat the test in 3–6 months.

Certain medications, such as glucocorticoids, thiazide diuretics, some HIV medications, and atypical antipsychotics, are known to increase the risk of diabetes and should be considered when deciding whether to screen.

3. Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes

Recommendation

- 3.1 At least annual monitoring for the development of type 2 diabetes in those with prediabetes is suggested. E

Lifestyle Behavior Change for Diabetes Prevention

Recommendations

- 3.2 Refer patients with prediabetes to an intensive lifestyle behavior change program modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) to achieve and maintain 7% loss of initial body weight and increase moderate-intensity physical activity (such as brisk walking) to at least 150 minutes/week. A

- 3.3 A variety of eating patterns can be considered to prevent diabetes in individuals with prediabetes. B

- 3.4 Based on patient preference, certified technology-assisted diabetes prevention programs may be effective in preventing type 2 diabetes and should be considered. B

Delivery and Dissemination of Lifestyle Behavior Change for Diabetes Prevention

The DPP research trial demonstrated that an intensive lifestyle intervention could reduce the risk of incident type 2 diabetes by 58% over 3 years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP), a resource designed to bring such evidence-based lifestyle change programs for preventing type 2 diabetes to communities (cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention).

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has expanded Medicare reimbursement coverage for the National DPP lifestyle intervention to organizations recognized by the CDC that become Medicare suppliers for this service. The locations of Medicare DPPs are available online at innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/medicare-diabetes-prevention-program/mdpp-map.

To qualify for Medicare coverage, patients must have a BMI in the overweight range and laboratory testing consistent with prediabetes in the last year. Medicaid coverage of the DPP lifestyle intervention is also expanding on a state-by-state basis.

Pharmacologic Interventions

Recommendation

- 3.6 Metformin therapy for prevention of type 2 diabetes should be considered in those with prediabetes, especially for those with BMI ≥35 kg/m 2 , those aged A

Metformin has the strongest evidence base and demonstrated long-term safety as a pharmacologic therapy for diabetes prevention. Other medications have been studied; no pharmacologic agent has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for diabetes prevention.

Prevention of Vascular Disease and Mortality

Recommendation

- 3.8 Prediabetes is associated with heightened cardiovascular (CV) risk; therefore, screening for and treatment of modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) are suggested. B

4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

A successful medical evaluation depends on beneficial interactions between the patient and a coordinated interdisciplinary team. Individuals with diabetes must assume an active role in their care. The patient, family or support people, physicians, and health care team should together formulate the management plan, which includes lifestyle management.

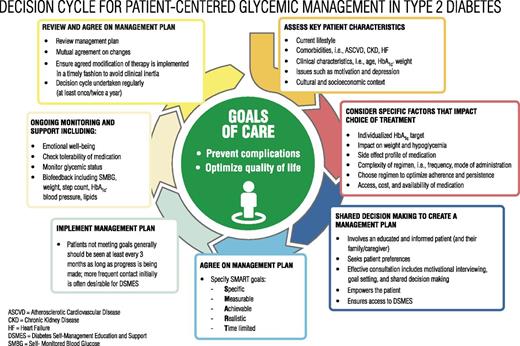

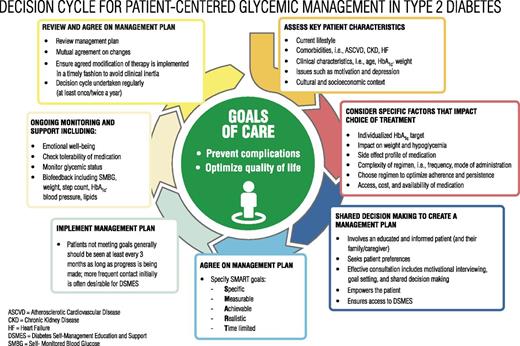

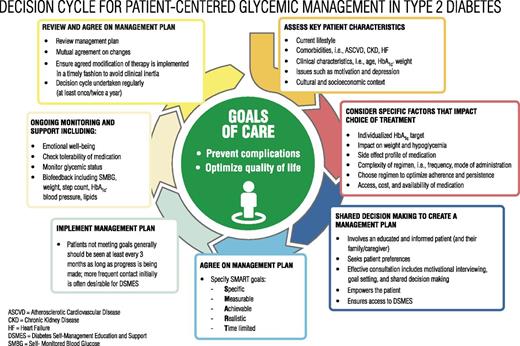

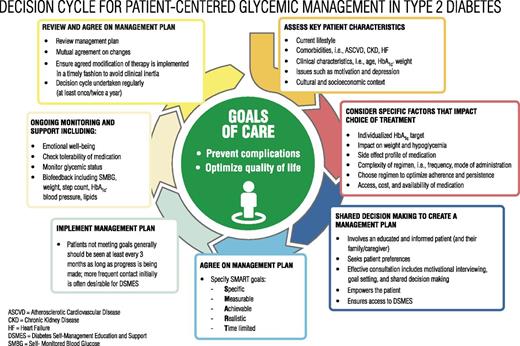

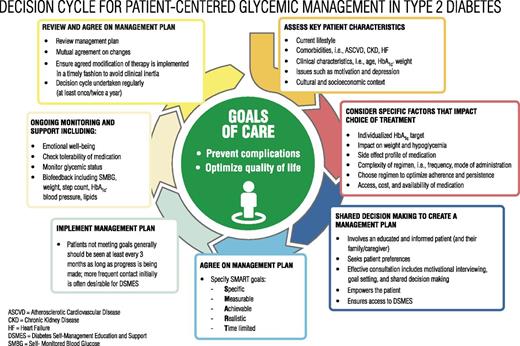

The goals of treatment for diabetes are to prevent or delay complications and optimize quality of life (Figure 4.1). Treatment goals and plans should be created with patients based on their individual preferences, values, and goals.

Decision cycle for patient-centered glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin. Reprinted from Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701.

Decision cycle for patient-centered glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin. Reprinted from Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701.

Recommendations

- 4.1 A patient-centered communication style that uses person-centered and strength-based language and active listening; elicits patient preferences and beliefs; and assesses literacy, numeracy, and potential barriers to care should be used to optimize patient health outcomes and health-related quality of life. B

- 4.2 People with diabetes can benefit from a coordinated multidisciplinary team that may draw from certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES), primary care providers, subspecialty providers, nurses, dietitians, exercise specialists, pharmacists, dentists, podiatrists, and mental health professionals. E

The use of empowering language can help to inform and motivate people, yet language that shames and judges may undermine this effort.

- Use language that is neutral, nonjudgmental, and based on facts, actions, or physiology/biology.

- Use language free from stigma.

- Use language that is strength based, respectful, and inclusive and that imparts hope.

- Use language that fosters collaboration between patients and providers.

- Use language that is person centered (e.g., “person with diabetes” is preferred over “diabetic”).

Comprehensive Medical Evaluation

Recommendations

- 4.3 A complete medical evaluation should be performed at the initial visit to:

- • Confirm the diagnosis and classify diabetes. A

- • Evaluate for diabetes complications and potential comorbid conditions. A

- • Review previous treatment and risk factor control in patients with established diabetes. A

- • Begin patient engagement in the formulation of a care management plan. A

- • Develop a plan for continuing care. A

- 4.4 A follow-up visit should include most components of the initial comprehensive medical evaluation. (See Table 4.1 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care.) A

- 4.5 Ongoing management should be guided by the assessment of overall health status, diabetes complications, CV risk (see “The Risk Calculator” in “10. CVD AND RISK MANAGEMENT”), hypoglycemia risk, and shared decision-making to set therapeutic goals. B

Immunizations

The importance of routine vaccinations for people living with diabetes has been elevated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Preventing avoidable infections not only directly prevents morbidity but also reduces hospitalizations, which may additionally reduce risk of acquiring infections such as COVID-19. Children and adults with diabetes should receive vaccinations according to age-appropriate recommendations.

Assessment of Comorbidities

Cognitive Impairment/Dementia

See “12. OLDER ADULTS.”

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Recommendation

- 4.10 Patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes and elevated liver enzymes (ALT) or fatty liver on ultrasound should be evaluated for presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. C

Cancer

Patients with diabetes should be encouraged to undergo recommended age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings and to reduce their modifiable cancer risk factors (obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking).

5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-Being to Improve Health Outcomes

Effective behavior management and psychological well-being are foundational to achieving treatment goals for people with diabetes. Essential to achieving these goals are DSMES, medical nutrition therapy (MNT), routine physical activity, smoking cessation counseling when needed, and psychosocial care.

DSMES

Recommendations

- 5.1 In accordance with the national standards for DSMES, all people with diabetes should participate in diabetes self-management education and receive the support needed to facilitate the knowledge, decision-making, and skills mastery necessary for diabetes self-care. A

- 5.2 There are four critical times to evaluate the need for diabetes self-management education to promote skills acquisition in support of regimen implementation, MNT, and well-being: at diagnosis, annually and/or when not meeting treatment targets, when complicating factors develop (medical, physical, psychosocial), and when transitions in life and care occur. E

- 5.3 Clinical outcomes, health status, and well-being are key goals of DSMES that should be measured as part of routine care. C

- 5.4 DSMES should be patient centered, may be given in group or individual settings and/or use technology, and should be communicated with the entire diabetes care team. A

- 5.5 Because DSMES can improve outcomes and reduce costs B, reimbursement by third-party payers is recommended. C

- 5.7 Some barriers to DSMES access may be mitigated through telemedicine approaches. B

Evidence suggests people with diabetes who completed more than 10 hours of DSMES over the course of 6–12 months and those who participated on an ongoing basis had significant reductions in mortality and A1C (decrease of 0.57%) compared with those who spent less time with a CDCES.

DSMES is associated with an increased use of primary care and preventive services and less frequent use of acute care and inpatient hospital services. Patients who participate in DSMES are more likely to follow best practice treatment recommendations, particularly among the Medicare population, and have lower Medicare and insurance claim costs.

MNT

All providers should refer people with diabetes for individualized MNT provided by a registered dietitian nutritionist (RD/RDN) who is knowledgeable and skilled in providing diabetes-specific MNT at diagnosis and as needed throughout the life span, similar to DSMES. MNT delivered by an RD/RDN is associated with A1C absolute decreases of 1.0–1.9% for people with type 1 diabetes and 0.3–2.0% for people with type 2 diabetes.

Eating Patterns and Meal Planning

Evidence suggests that there is not an ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and fat for people with diabetes. Therefore, macronutrient distribution should be based on an individualized assessment of current eating patterns, personal preferences (e.g., tradition, culture, religion, health beliefs and goals, and economics), and metabolic goals.

Weight Management

Lifestyle intervention programs should be intensive and have frequent follow-up to achieve significant reductions in excess body weight and improve clinical indicators.

For many individuals with overweight and obesity with type 2 diabetes, 5% weight loss is needed to achieve beneficial outcomes in glycemic control, lipids, and blood pressure. The clinical benefits of weight loss are progressive, and more intensive weight-loss goals (i.e., 15%) may be appropriate to maximize benefit depending on need, feasibility, and safety.

Physical Activity

Recommendations

- 5.26 Children and adolescents with type 1 or type 2 diabetes or prediabetes should engage in 60 minutes/day or more of moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, with vigorous muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities at least 3 days/week. C

- 5.27 Most adults with type 1 C and type 2 B diabetes should engage in 150 minutes or more of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, spread over at least 3 days/week, with no more than 2 consecutive days without activity. Shorter durations (minimum 75 minutes/week) of vigorous-intensity or interval training may be sufficient for younger and more physically fit individuals.

- 5.28 Adults with type 1 C and type 2 B diabetes should engage in 2–3 sessions/week of resistance exercise on nonconsecutive days.

- 5.29 All adults, and particularly those with type 2 diabetes, should decrease the amount of time spent in daily sedentary behavior. B Prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 minutes for blood glucose benefits. C

- 5.30 Flexibility training and balance training are recommended 2–3 times/week for older adults with diabetes. Yoga and tai chi may be included based on individual preferences to increase flexibility, muscular strength, and balance. C

- 5.31 Evaluate baseline physical activity and sedentary time. Promote increase in nonsedentary activities above baseline for sedentary individuals with type 1 B and type 2 E diabetes. Examples include walking, yoga, housework, gardening, swimming, and dancing.

Exercise in the Presence of Microvascular Complications

Retinopathy

If proliferative diabetic retinopathy or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, then vigorous-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated because of the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment. Consultation with an ophthalmologist prior to engaging in an intense exercise regimen may be appropriate.

Peripheral Neuropathy

Decreased pain sensation and a higher pain threshold in the extremities can result in an increased risk of skin breakdown, infection, and Charcot joint destruction with some forms of exercise. All individuals with peripheral neuropathy should wear proper footwear and examine their feet daily to detect lesions early. Anyone with a foot injury or open sore should be restricted to non–weight-bearing activities.

Autonomic Neuropathy

Individuals with diabetic autonomic neuropathy should undergo cardiac investigation before beginning physical activity more intense than that to which they are accustomed.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Physical activity can acutely increase urinary albumin excretion. However, there is no evidence that vigorous-intensity exercise accelerates the rate of progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), and there appears to be no need for specific exercise restrictions for people with DKD in general.

Smoking Cessation: Tobacco and E-Cigarettes

Recommendations

- 5.32 Advise all patients not to use cigarettes and other tobacco products A or e-cigarettes. A

- 5.33 After identification of tobacco or e-cigarette use, include smoking cessation counseling and other forms of treatment as a routine component of diabetes care. A

Psychosocial Issues

Recommendations

- 5.35 Psychosocial care should be integrated with a collaborative, patient-centered approach and provided to all people with diabetes, with the goals of optimizing health outcomes and health-related quality of life. A

- 5.36 Psychosocial screening and follow-up may include, but are not limited to, attitudes about diabetes, expectations for medical management and outcomes, affect or mood, general and diabetes-related quality of life, available resources (financial, social, and emotional), and psychiatric history. E

- 5.37 Providers should consider assessment for symptoms of diabetes distress, depression, anxiety, disordered eating, and cognitive capacities using appropriate standardized and validated tools at the initial visit, at periodic intervals, and when there is a change in disease, treatment, or life circumstance. Including caregivers and family members in this assessment is recommended. B

- 5.38 Consider screening older adults (aged ≥65 years) with diabetes for cognitive impairment and depression. B

Diabetes Distress

Recommendation

- 5.39 Routinely monitor people with diabetes for diabetes distress, particularly when treatment targets are not met and/or at the onset of diabetes complications. B

Diabetes distress refers to significant negative psychological reactions related to emotional burdens and worries specific to an individual's experience in having to manage a severe, complicated, and demanding chronic disease such as diabetes. The constant behavioral demands of diabetes self-management and the potential or actuality of disease progression are directly associated with reports of diabetes distress.

See “5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-Being to Improve Health Outcomes” in the complete 2021 Standards of Care for information on anxiety disorders (including fear of hypoglycemia), depression, disordered eating, and serious mental illness, as well as information about referral to a mental health professional.

6. Glycemic Targets

Assessment of Glycemic Control

Glycemic control is assessed by the A1C measurement, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). Clinical trials primarily use A1C as the metric to demonstrate the benefits of improved glycemic control. CGM serves an important role in assessing the effectiveness and safety of treatment in many patients with type 1 diabetes, including prevention of hypoglycemia, and in patients with type 2 diabetes on intensive insulin regimens and with hypoglycemia. Patient SMBG can be used with self-management and medication adjustment, particularly in individuals taking insulin.

Glycemic Assessment

Recommendations

- 6.1 Assess glycemic status (A1C or other glycemic measurement) at least two times a year in patients who are meeting treatment goals (and who have stable glycemic control). E

- 6.2 Assess glycemic status at least quarterly, and as needed, in patients whose therapy has recently changed and/or who are not meeting glycemic goals. E

Glucose Assessment by CGM

Recommendations

- 6.3 Standardized, single-page glucose reports from CGM devices with visual cues, such as the ambulatory glucose profile (AGP), should be considered as a standard printout for all CGM devices. E

- 6.4 Time in range (TIR) is associated with the risk of microvascular complications, should be an acceptable end point for clinical trials moving forward, and can be used for assessment of glycemic control. Additionally, time below target (180 mg/dL [10.0 mmol/L]) are useful parameters for reevaluation of the treatment regimen. C

For many people with diabetes, glucose monitoring is key for achieving glycemic targets. It allows patients to evaluate their individual response to therapy and assess whether glycemic targets are being safely achieved.

CGM technology has grown rapidly and is more accessible and accurate. The Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) and data on TIR, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia are available to providers and patients via standardized reports such as the AGP (Figure 6.1). Visual cues and recommendations are offered to assist in data interpretation and treatment decision-making.

Key points included in standard AGP report. Adapted from Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603.

Key points included in standard AGP report. Adapted from Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603.

Glycemic Goals

Recommendations

- 6.5a An A1C goal for many nonpregnant adults of A

- 6.5b If using AGP/GMI to assess glycemia, a parallel goal is a TIR of >70% with time below range B

- 6.6 On the basis of provider judgment and patient preference, achievement of lower A1C levels than the goal of 7% may be acceptable, and even beneficial, if it can be achieved safely without significant hypoglycemia or other adverse effects of treatment. C

- 6.7 Less stringent A1C goals (such as B

Reassess glycemic targets over time based on patient and disease factors. (See Figure 6.2 and Table 12.1 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care.) Table 6.3 summarizes glycemic recommendations for many nonpregnant adults. For specific guidance, see “6. Glycemic Targets,” “13. Children and Adolescents,” and “14. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy” in the complete 2021 Standards of Care.

Summary of Glycemic Recommendations for Many Nonpregnant Adults With Diabetes

| . | . |

| A1C | |

| Preprandial capillary plasma glucose | 80–130 mg/dL* (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) |

| Peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose† | |

| . | . |

| A1C | |

| Preprandial capillary plasma glucose | 80–130 mg/dL* (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) |

| Peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose† | |

More or less stringent glycemic goals may be appropriate for individual patients. #CGM may be used to assess glycemic target as noted in Recommendation 6.5b and Figure 6.1. Goals should be individualized based on duration of diabetes, age/life expectancy, comorbid conditions, known CVD or advanced microvascular complications, hypoglycemia unawareness, and individual patient considerations. †Postprandial glucose may be targeted if A1C goals are not met despite reaching preprandial glucose goals. Postprandial glucose measurements should be made 1–2 hours after the beginning of the meal, generally peak levels in patients with diabetes.

CGM may be used to assess glycemic target as noted in Recommendation 6.5b and Figure 6.1. Goals should be individualized based on duration of diabetes, age/life expectancy, comorbid conditions, known CVD or advanced microvascular complications, hypoglycemia unawareness, and individual patient considerations.

Postprandial glucose may be targeted if A1C goals are not met despite reaching preprandial glucose goals. Postprandial glucose measurements should be made 1–2 hours after the beginning of the meal, generally peak levels in patients with diabetes.

Hypoglycemia

The classification of hypoglycemia level is defined in Table 6.4.

Classification of Hypoglycemia

| . | Glycemic Criteria/Description . |

| Level 1 | Glucose |

| Level 2 | Glucose |

| Level 3 | A severe event characterized by altered mental and/or physical status requiring assistance for treatment of hypoglycemia |

| . | Glycemic Criteria/Description . |

| Level 1 | Glucose |

| Level 2 | Glucose |

| Level 3 | A severe event characterized by altered mental and/or physical status requiring assistance for treatment of hypoglycemia |

Reprinted from Agiostratidou G, Anhalt H, Ball D, et al. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1622–1630.

Recommendations

- 6.9 Occurrence and risk for hypoglycemia should be reviewed at every encounter and investigated as indicated. C

- 6.10 Glucose (∼15–20 g) is the preferred treatment for the conscious individual with blood glucose B

- 6.11 Glucagon should be prescribed for all individuals at increased risk of level 2 or 3 hypoglycemia so that it is available should it be needed. Caregivers, school personnel, or family members of these individuals should know where it is and when and how to administer it. Glucagon administration is not limited to health care professionals. E

- 6.12 Hypoglycemia unawareness or one or more episodes of level 3 hypoglycemia should trigger hypoglycemia avoidance education and reevaluation of the treatment regimen. E

- 6.13 Insulin-treated patients with hypoglycemia unawareness, one level 3 hypoglycemic event, or a pattern of unexplained level 2 hypoglycemia should be advised to raise their glycemic targets to strictly avoid hypoglycemia for at least several weeks in order to partially reverse hypoglycemia unawareness and reduce risk of future episodes. A

- 6.14 Ongoing assessment of cognitive function is suggested with increased vigilance for hypoglycemia by the clinician, patient, and caregivers if low cognition or declining cognition is found. B

7. Diabetes Technology

Diabetes technology describes the devices, software, and hardware used to manage diabetes. It includes delivery systems such as insulin pumps, pens, and syringes as well as CGM devices and glucose meters. Newer forms of diabetes technology include hybrid devices that both monitor glucose and deliver insulin, sometimes via automated algorithms. Mobile applications and software provide diabetes self-management support. Increased patient interest has increased the use of diabetes technology in the primary care setting.

Recommendation

- 7.1 Use of technology should be individualized based on a patient’s needs, desires, skill level, and availability of devices. E

SMBG

Recommendations

- 7.2 People who are on insulin using SMBG should be encouraged to test when appropriate based on their insulin regimen. This may include testing when fasting, prior to meals and snacks, at bedtime, prior to exercise, when low blood glucose is suspected, after treating low blood glucose until they are normoglycemic, and prior to and while performing critical tasks such as driving. B

- 7.4 When prescribed as part of a DSMES program, SMBG may help to guide treatment decisions and/or self-management for patients taking less frequent insulin injections. B

CGM Devices

See Table 7.3 for definitions of types of CGM devices.

| Type of CGM . | Description . |

|---|

| Real-time CGM | CGM systems that measure and display glucose levels continuously |

| Intermittently scanned CGM | CGM systems that measure glucose levels continuously but only display glucose values when swiped by a reader or a smartphone |

| Professional CGM | CGM devices that are placed on the patient in the provider’s office (or with remote instruction) and worn for a discrete period of time (generally 7–14 days). Data may be blinded or visible to the person wearing the device. The data are used to assess glycemic patterns and trends. These devices are not fully owned by the patient—they are a clinic-based device, as opposed to the patient-owned real-time or intermittently scanned CGM devices. |

| Type of CGM . | Description . |

|---|

| Real-time CGM | CGM systems that measure and display glucose levels continuously |

| Intermittently scanned CGM | CGM systems that measure glucose levels continuously but only display glucose values when swiped by a reader or a smartphone |

| Professional CGM | CGM devices that are placed on the patient in the provider’s office (or with remote instruction) and worn for a discrete period of time (generally 7–14 days). Data may be blinded or visible to the person wearing the device. The data are used to assess glycemic patterns and trends. These devices are not fully owned by the patient—they are a clinic-based device, as opposed to the patient-owned real-time or intermittently scanned CGM devices. |

Recommendations

- 7.11 In patients on a multiple daily injection (MDI) or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) regimen, real-time CGM devices should be used as close to daily as possible for maximal benefit. A Intermittently scanned CGM devices should be scanned frequently, at a minimum once every 8 hours.

- 7.12 When used as an adjunct to pre- and postprandial SMBG, CGM can help to achieve A1C targets in diabetes and pregnancy. B

Data derived by CGM allows providers to analyze patient data using new metrics for glycemic targets. These metrics include average blood glucose, percentage of TIR (70–180 mg/dL), glycemic variability, and percentage of time spent above and below range.

Combined Insulin Pump and Sensor Systems

See “7. Diabetes Technology” in the complete 2021 Standards of Care for more information.

The Future

Diabetes technology must be adapted for the individual needs of the patient. Education is essential to ensure that patients can appropriately engage with their diabetes devices to reap the potential health benefits. Both patients and providers must have realistic expectations and understand the capabilities of these new technologies.

8. Obesity Management for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes

Strong evidence exists that treatment of obesity can slow the progression of prediabetes to diabetes and benefit those with type 2 diabetes. Modest and sustained weight loss has been shown to improve glycemic control and reduce the need for glucose-lowering medications.

Assessment

Recommendations

- 8.1 Use patient-centered, nonjudgmental language that fosters collaboration between patients and providers, including people-first language (e.g., “person with obesity” rather than “obese person”). E

- 8.2 Measure height and weight and calculate BMI at annual visits or more frequently. Assess weight trajectory to inform treatment considerations. E

- 8.3 Based on clinical considerations, such as the presence of comorbid heart failure (HF) or significant unexplained weight gain or loss, weight may need to be monitored and evaluated more frequently. B If deterioration of medical status is associated with significant weight gain or loss, inpatient evaluation should be considered, especially focused on associations between medication use, food intake, and glycemic status. E

- 8.4 Accommodations should be made to provide privacy during weighing. E

Use BMI to document weight status. Providers should advise patients that higher BMIs increase the risks of diabetes, CVD, all-cause mortality, and adverse quality of life outcomes. Providers should assess patients’ readiness to engage in behavior changes for weight loss. Shared decision-making should be used to determine behavioral and weight-loss goals and patient-appropriate intervention strategies.

Diet, Physical Activity, and Behavioral Therapy

Recommendations

- 8.5 Diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy designed to achieve and maintain ≥5% weight loss is recommended for most patients with type 2 diabetes who have overweight or obesity and are ready to achieve weight loss. Greater benefits in control of diabetes and CV risk may be gained from even greater weight loss. B

- 8.6 Such interventions should include a high frequency of counseling (≥16 sessions in 6 months) and focus on dietary changes, physical activity, and behavioral strategies to achieve a 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit. A

- 8.7 An individual’s preferences, motivation, and life circumstances should be considered, along with medical status, when weight-loss interventions are recommended. C

- 8.8 Behavioral changes that create an energy deficit, regardless of macronutrient composition, will result in weight loss. Dietary recommendations should be individualized to the patient’s preferences and nutritional needs. A

- 8.9 Evaluate systemic, structural, and socioeconomic factors that may impact dietary patterns and food choices, such as food insecurity and hunger, access to healthful food options, cultural circumstances, and SDOH. C

- 8.10 For patients who achieve short-term weight-loss goals, long-term (≥1 year) weight-maintenance programs are recommended when available. Such programs should, at minimum, provide monthly contact and support, recommend ongoing monitoring of body weight (weekly or more frequently) and other self-monitoring strategies, and encourage high levels of physical activity (200–300 minutes/week). A

- 8.11 Short-term dietary intervention using structured, very-low-calorie diets (800–1,000 kcal/day) may be prescribed for carefully selected patients by trained practitioners in medical settings with close monitoring. Long-term, comprehensive weight-maintenance strategies and counseling should be integrated to maintain weight loss. B

Among patients with both type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity who have inadequate glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid control and/or other obesity-related medical conditions, modest and sustained weight loss improves glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipids and may reduce the need for medications to control these risk factors.

Pharmacotherapy

Recommendations

- 8.12 When choosing glucose-lowering medications for patients with type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity, consider the medication's effect on weight. B

- 8.13 Whenever possible, minimize medications for comorbid conditions that are associated with weight gain. E

- 8.14 Weight-loss medications are effective as adjuncts to diet, physical activity, and behavioral counseling for selected patients with type 2 diabetes and BMI ≥27 kg/m 2 . Potential benefits and risks must be considered. A

- 8.15 If a patient’s response to weight-loss medication is effective (typically defined as >5% weight loss after 3 months’ use), further weight loss is likely with continued use. When early response is insufficient (typically A

Nearly all FDA-approved medications for weight loss have been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and delay progression to diabetes for those at risk. Table 8.2 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care provides information on FDA-approved medications for obesity.

Given the high cost, limited insurance coverage, and paucity of data in people with diabetes, medical devices for weight loss are not considered to be the standard of care for obesity management in people with type 2 diabetes.

Metabolic Surgery

Recommendations

- 8.16 Metabolic surgery should be a recommended option to treat type 2 diabetes in screened surgical candidates with BMI ≥40 kg/m 2 (BMI ≥37.5 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) and in adults with BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m 2 (32.5–37.4 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) who do not achieve durable weight loss and improvement in comorbidities (including hyperglycemia) with nonsurgical methods. A

- 8.17 Metabolic surgery may be considered as an option to treat type 2 diabetes in adults with BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m 2 (27.5–32.4 kg/m 2 in Asian Americans) who do not achieve durable weight loss and improvement in comorbidities (including hyperglycemia) with nonsurgical methods. A

- 8.18 Metabolic surgery should be performed in high-volume centers with multidisciplinary teams knowledgeable about and experienced in the management of diabetes and gastrointestinal surgery. E

- 8.19 Long-term lifestyle support and routine monitoring of micronutrient and nutritional status must be provided to patients after surgery, according to guidelines for postoperative management of metabolic surgery by national and international professional societies. C

- 8.20 People being considered for metabolic surgery should be evaluated for comorbid psychological conditions and social and situational circumstances that have the potential to interfere with surgery outcomes. B

- 8.21 People who undergo metabolic surgery should routinely be evaluated to assess the need for ongoing mental health services to help with the adjustment to medical and psychosocial changes after surgery. C

A substantial body of evidence has now been accumulated, including data from numerous randomized controlled (nonblinded) clinical trials, demonstrating that metabolic surgery achieves superior glycemic control and reduction of CV risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with various lifestyle/medical interventions.

Longer-term concerns include dumping syndrome (nausea, colic, and diarrhea), vitamin and mineral deficiencies, anemia, osteoporosis, and severe hypoglycemia. Long-term nutritional and micronutrient deficiencies and related complications occur with variable frequency depending on the type of procedure and require lifelong vitamin/nutritional supplementation; thus, long-term lifestyle support and routine monitoring of micronutrient and nutritional status should be provided to patients after surgery.

9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment

Pharmacologic Therapy for Type 1 Diabetes

Recommendations

- 9.1 Most people with type 1 diabetes should be treated with MDI of prandial and basal insulin or CSII. A

- 9.2 Most individuals with type 1 diabetes should use rapid-acting insulin analogs to reduce hypoglycemia risk. A

- 9.3 Patients with type 1 diabetes should receive education on how to match prandial insulin doses to carbohydrate intake, premeal blood glucose, and anticipated physical activity. C

See “9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment” in the complete 2021 Standards of Care for more detailed information on pharmacologic approaches to type 1 diabetes management.

Pharmacologic Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes

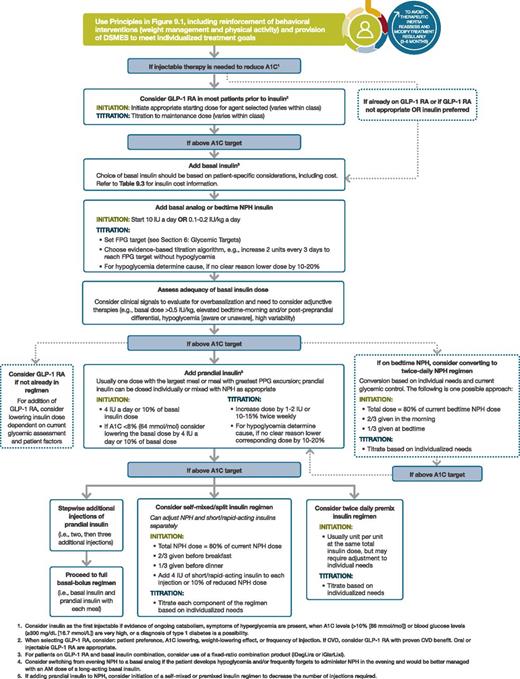

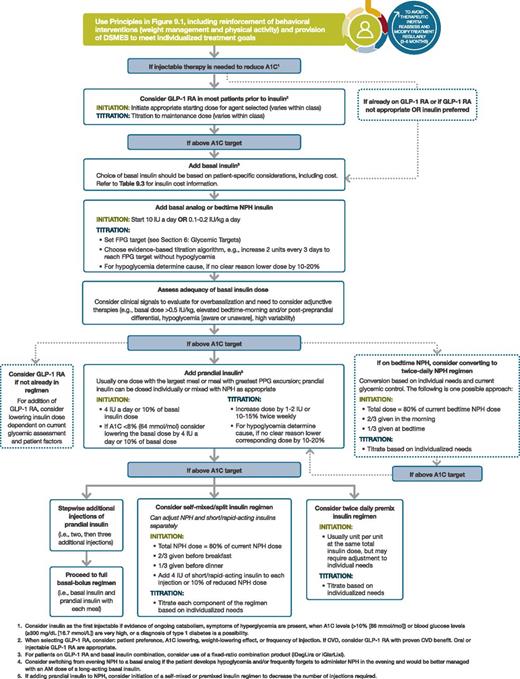

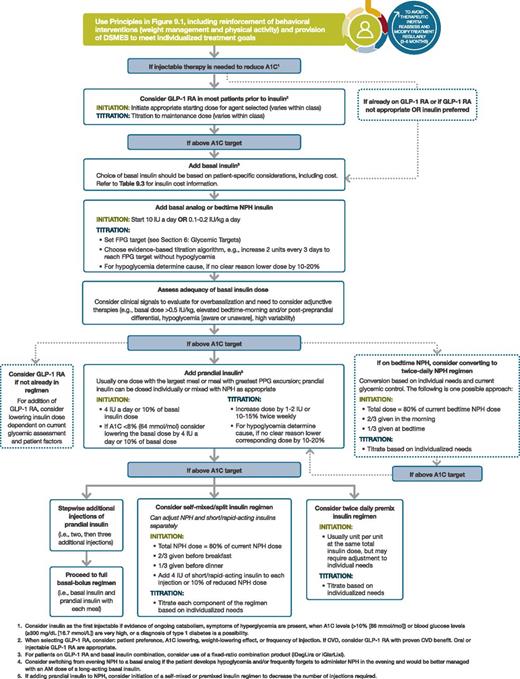

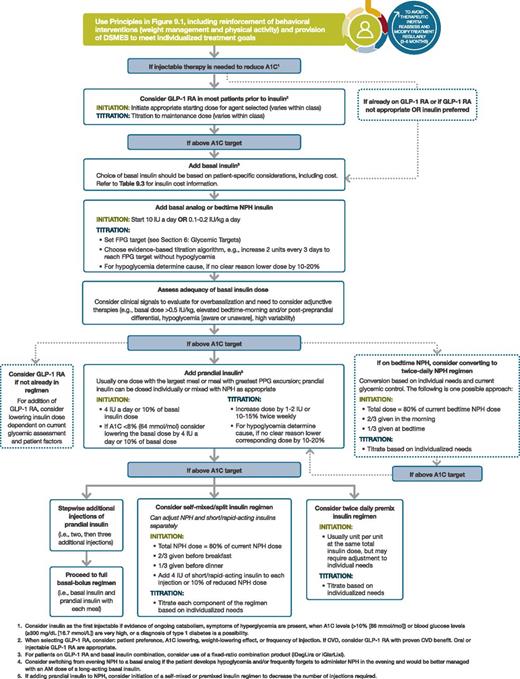

Figure 9.1, Figure 9.2, and Table 9.1 provide details for informed decision-making on pharmacologic agents for type 2 diabetes.

Glucose-lowering medication in type 2 diabetes: 2021 ADA Professional Practice Committee adaptation of Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41: 2669–2701 and Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. Diabetes Care 2020;43:487–493. For appropriate context, see Figure 4.1. In this version, the “Indicators of high-risk or established ASCVD, CKD, or HF” pathway was adapted based on trial populations studied. DPP-4i, DPP-4 inhibitor; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SGLT2i, SGLT2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea; T2D, type 2 diabates; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Glucose-lowering medication in type 2 diabetes: 2021 ADA Professional Practice Committee adaptation of Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41: 2669–2701 and Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. Diabetes Care 2020;43:487–493. For appropriate context, see Figure 4.1. In this version, the “Indicators of high-risk or established ASCVD, CKD, or HF” pathway was adapted based on trial populations studied. DPP-4i, DPP-4 inhibitor; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SGLT2i, SGLT2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea; T2D, type 2 diabates; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Intensifying to injectable therapies. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FRC, fixed-ratio combination; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; max, maximum; PPG, postprandial glucose. Adapted from Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701.

Intensifying to injectable therapies. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FRC, fixed-ratio combination; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; max, maximum; PPG, postprandial glucose. Adapted from Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701.

Drug-specific and patient factors to consider when selecting antihyperglycemic treatment in adults with type 2 diabetes

*For agent-specific dosing recommendations, please refer to the manufacturers’ prescribing information. †FDA-approved for CVD benefit. ‡FDA-approved for HF indication. §FDA-approved for CKD indication. GI, gastrointestinal; GLP-1 RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; SQ, subcutaneous; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Recommendations

- 9.4 Metformin is the preferred initial pharmacologic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. A

- 9.5 Once initiated, metformin should be continued as long as it is tolerated and not contraindicated; other agents, including insulin, should be added to metformin. A

- 9.6 Early combination therapy can be considered in some patients at treatment initiation to extend the time to treatment failure. A

- 9.7 The early introduction of insulin should be considered if there is evidence of ongoing catabolism (weight loss), if symptoms of hyperglycemia are present, or when A1C levels (>10% [86 mmol/mol]) or blood glucose levels (≥300 mg/dL [16.7 mmol/L]) are very high. E

- 9.8 A patient-centered approach should be used to guide the choice of pharmacologic agents. Considerations include effect on CV and renal comorbidities, efficacy, hypoglycemia risk, impact on weight, cost, risk for side effects, and patient preferences (Table 9.1 and Figure 9.1). E

- 9.9 Among patients with type 2 diabetes who have established atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) or indicators of high risk, established kidney disease, or HF, a sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist with demonstrated CVD benefit (Table 9.1) is recommended as part of the glucose-lowering regimen independent of A1C and in consideration of patient-specific factors. (See Figure 9.1 and “10. CVD AND RISK MANAGEMENT.”) A

- 9.10 In patients with type 2 diabetes, a GLP-1 receptor agonist is preferred to insulin when possible. A

- 9.11 Recommendation for treatment intensification for patients not meeting treatment goals should not be delayed. A

- 9.12 The medication regimen and medication-taking behavior should be reevaluated at regular intervals (every 3–6 months) and adjusted as needed to incorporate specific factors that impact choice of treatment (Figure 4.1 and Table 9.1). E

- 9.13 Clinicians should be aware of the potential for overbasalization with insulin therapy. Clinical signals that may prompt evaluation of overbasalization include basal dose more than ∼0.5 IU/kg, high bedtime-morning or post-preprandial glucose differential, hypoglycemia (aware or unaware), and high variability. Indication of overbasalization should prompt reevaluation to further individualize therapy. E

10. CVD and Risk Management

ASCVD—defined as coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral arterial disease (PAD) presumed to be of atherosclerotic origin—is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people with diabetes. HF is another major cause of morbidity and mortality from CVD. For prevention and management of both ASCVD and HF, CV risk factors should be assessed at least annually in all patients with diabetes. These risk factors include obesity/overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the presence of albuminuria.

The Risk Calculator

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD risk calculator (Risk Estimator Plus) is a useful tool to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk (tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus).

Hypertension/Blood Pressure Control

Hypertension, defined as a sustained blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, is common among patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Recommendations

Screening and Diagnosis

- 10.1 Blood pressure should be measured at every routine clinical visit. Patients found to have elevated blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg) should have blood pressure confirmed using multiple readings, including measurements on a separate day, to diagnose hypertension. B

- 10.2 All hypertensive patients with diabetes should monitor their blood pressure at home. B

Treatment Goals

- 10.3 For patients with diabetes and hypertension, blood pressure targets should be individualized through a shared decision-making process that addresses CV risk, potential adverse effects of antihypertensive medications, and patient preferences. C

- 10.4 For individuals with diabetes and hypertension at higher CV risk (existing ASCVD or 10-year ASCVD risk ≥15%), a blood pressure target of C

- 10.5 For individuals with diabetes and hypertension at lower risk for CVD (10-year ASCVD risk <15%), treat to a blood pressure target of <140/90 mmHg. A

Treatment Strategies

Lifestyle Intervention

Recommendation

- 10.7 For patients with blood pressure >120/80 mmHg, lifestyle intervention consists of weight loss when indicated, a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style eating pattern including reducing sodium and increasing potassium intake, moderation of alcohol intake, and increased physical activity. A

Pharmacologic Interventions

Recommendations

- 10.8 Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of pharmacologic therapy to achieve blood pressure goals. A

- 10.9 Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of two drugs or a single-pill combination of drugs demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes. A

- 10.10 Treatment for hypertension should include drug classes demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes. A ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are recommended first-line therapy for hypertension in people with diabetes and coronary artery disease (CAD). A

- 10.11 Multiple-drug therapy is generally required to achieve blood pressure targets. However, combinations of ACE inhibitors and ARBs and combinations of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with direct renin inhibitors should not be used. A

- 10.12 An ACE inhibitor or ARB, at the maximum tolerated dose indicated for blood pressure treatment, is the recommended first-line treatment for hypertension in patients with diabetes and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥300 mg/g creatinine A or 30–299 mg/g creatinine. B If one class is not tolerated, the other should be substituted. B

- 10.13 For patients treated with an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or diuretic, serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum potassium levels should be monitored at least annually. B

- 10.14 Patients with hypertension who are not meeting blood pressure targets on three classes of antihypertensive medications (including a diuretic) should be considered for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy. B

Multiple-drug therapy is often required to achieve blood pressure targets, particularly in the setting of DKD. Titration of and/or addition of further blood pressure medications should be made in a timely fashion to overcome therapeutic inertia in achieving blood pressure goals. (See Figure 10.1 in the complete 2021 Standards of Care.)

Lipid Management

Lifestyle Intervention

Recommendations

- 10.15 Lifestyle modification focusing on weight loss (if indicated); application of a Mediterranean style or DASH eating pattern; reduction of saturated fat and trans fat; increase of dietary n-3 fatty acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols/sterols intake; and increased physical activity should be recommended to improve the lipid profile and reduce the risk of developing ASCVD in patients with diabetes. A

- 10.16 Intensify lifestyle therapy and optimize glycemic control for patients with elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL [1.7 mmol/L]) and/or low HDL cholesterol (C

Ongoing Therapy and Monitoring With Lipid Panel

Recommendations

- 10.17 In adults not taking statins or other lipid-lowering therapy, it is reasonable to obtain a lipid profile at the time of diabetes diagnosis, at an initial medical evaluation, and every 5 years thereafter if under the age of 40 years, or more frequently if indicated. E

- 10.18 Obtain a lipid profile at initiation of statins or other lipid-lowering therapy, 4–12 weeks after initiation or a change in dose, and annually thereafter as it may help to monitor the response to therapy and inform medication adherence. E

Statin Treatment

Primary Prevention

Recommendations

- 10.19 For patients with diabetes aged 40–75 years without ASCVD, use moderate-intensity statin therapy in addition to lifestyle therapy. A

- 10.20 For patients with diabetes aged 20–39 years with additional ASCVD risk factors, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy in addition to lifestyle therapy. C

- 10.21 In patients with diabetes at higher risk, especially those with multiple ASCVD risk factors or aged 50–70 years, it is reasonable to use high-intensity statin therapy. B

- 10.22 In adults with diabetes and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL cholesterol levels by 50% or more. C

Secondary Prevention

Recommendations

- 10.23 For patients of all ages with diabetes and ASCVD, high-intensity statin therapy should be added to lifestyle therapy. A

- 10.24 For patients with diabetes and ASCVD considered very high risk using specific criteria, if LDL cholesterol is ≥70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin dose, consider adding additional LDL-lowering therapy (such as ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitor). A Ezetimibe may be preferred due to lower cost.

- 10.25 For patients who do not tolerate the intended intensity, the maximally tolerated statin dose should be used. E

- 10.26 In adults with diabetes aged >75 years already on statin therapy, it is reasonable to continue statin treatment. B

- 10.27 In adults with diabetes aged >75 years, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy after discussion of potential benefits and risks. C

- 10.28 Statin therapy is contraindicated in pregnancy. B

Patients with type 2 diabetes have an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities, contributing to their high risk of ASCVD. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated the beneficial effects of statin therapy on ASCVD outcomes in subjects with and without CHD. Statins are the drugs of choice for LDL cholesterol lowering and cardioprotection. High-intensity statin therapy will achieve a reduction of approximately ≥50% in LDL cholesterol, and moderate-intensity statin regimens achieve 30–49% reductions in LDL cholesterol.

Treatment of Other Lipoprotein Fractions or Targets

Recommendations

- 10.29 For patients with fasting triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL, evaluate for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia and consider medical therapy to reduce the risk of pancreatitis. C

- 10.30 In adults with moderate hypertriglyceridemia (fasting or nonfasting triglycerides 175–499 mg/dL), clinicians should address and treat lifestyle factors (obesity and metabolic syndrome), secondary factors (diabetes, chronic liver or kidney disease and/or nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism), and medications that raise triglycerides. C

- 10.31 In patients with ASCVD or other CV risk factors on a statin with controlled LDL cholesterol but elevated triglycerides (135–499 mg/dL), the addition of icosapent ethyl can be considered to reduce CV risk. A

Other Combination Therapy

Recommendations

- 10.32 Statin plus fibrate combination therapy has not been shown to improve ASCVD outcomes and is generally not recommended. A

- 10.33 Statin plus niacin combination therapy has not been shown to provide additional CV benefit above statin therapy alone, may increase the risk of stroke with additional side effects, and is generally not recommended. A

Diabetes Risk With Statin Use

A meta-analysis of 13 randomized statin trials with 91,140 participants showed an odds ratio of 1.09 for a new diagnosis of diabetes, so that (on average) treatment of 255 patients with statins for 4 years resulted in one additional case of diabetes while simultaneously preventing 5.4 vascular events among those 255 patients.

Lipid-Lowering Agents and Cognitive Function

The most recent systematic review of the FDA’s post-marketing surveillance databases, randomized controlled trials, and cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies evaluating cognition in patients receiving statins found that published data do not reveal an adverse effect of statins on cognition.

Antiplatelet Agents

Recommendations

- 10.34 Use aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) as a secondary prevention strategy in those with diabetes and a history of ASCVD. A

- 10.35 For patients with ASCVD and documented aspirin allergy, clopidogrel (75 mg/day) should be used. B

- 10.36 Dual antiplatelet therapy (with low-dose aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor) is reasonable for a year after an acute coronary syndrome and may have benefits beyond this period. A

- 10.37 Long-term treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy should be considered for patients with prior coronary intervention, high ischemic risk, and low bleeding risk to prevent major adverse CV events (MACE). A

- 10.38 Combination therapy with aspirin plus low-dose rivaroxaban should be considered for patients with stable coronary and/or PAD and low bleeding risk to prevent major adverse limb and CV events. A

- 10.39 Aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) may be considered as a primary prevention strategy in those with diabetes who are at increased CV risk, after a comprehensive discussion with the patient on the benefits versus the comparable increased risk of bleeding. A

Risk Reduction

Aspirin is effective in reducing CV morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke (secondary prevention) and is strongly recommended.

In primary prevention, however, the benefit is more controversial. The use of aspirin needs to be carefully considered in the context of shared decision-making, weighing the CV benefits with the fairly comparable increase in risk of bleeding; generally, it may not be recommended. Aspirin may be considered in the context of high CV risk with low bleeding risk, but generally not in older adults. Aspirin is not recommended for those at low risk of ASCVD (such as men and women aged

CVD

Recommendations

Screening

- 10.40 In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for CAD is not recommended, as it does not improve outcomes as long as ASCVD risk factors are treated. A

- 10.41 Consider investigations for CAD in the presence of any of the following: atypical cardiac symptoms (e.g., unexplained dyspnea, chest discomfort); signs or symptoms of associated vascular disease, including carotid bruits, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, or PAD; or electrocardiogram abnormalities (e.g., Q waves). E

Treatment

- 10.42 Among patients with type 2 diabetes who have established ASCVD or established kidney disease, an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CVD benefit (see Tables 10.3B and 10.3C in the complete 2021 Standards of Care) is recommended as part of the comprehensive CV risk reduction and/or glucose-lowering regimens. A

- 10.42a In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD, multiple ASCVD risk factors, or DKD, an SGLT2 inhibitor with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE and/or HF hospitalization. A

- 10.42b In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or multiple risk factors for ASCVD, a GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE. A

- 10.43 In patients with type 2 diabetes and established HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven benefit in this patient population is recommended to reduce risk of worsening HF and CV death. A

- 10.44 In patients with known ASCVD, particularly CAD, ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy is recommended to reduce the risk of CV events. A

- 10.45 In patients with prior MI, β-blockers should be continued for 3 years after the event. B

- 10.46 Treatment of patients with HFrEF should include a β-blocker with proven CV outcomes benefit, unless otherwise contraindicated. A

- 10.47 In patients with type 2 diabetes with stable HF, metformin may be continued for glucose lowering if eGFR remains >30 mL/min/1.73 m 2 but should be avoided in unstable or hospitalized patients with HF. B

CV outcomes trials (CVOTs) of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors have all, so far, not shown CV benefits relative to placebo. Numerous large randomized controlled trials have reported statistically significant reductions in CV events for three of the FDA-approved SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin) and four FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists (liraglutide, albiglutide [although that agent was removed from the market for business reasons], semaglutide [lower risk of CV events in a moderate-sized clinical trial but one not powered as a CVOT], and dulaglutide). SGLT2 inhibitors also appear to reduce risk of HF hospitalization and progression of kidney disease in patients with established ASCVD, multiple risk factors for ASCVD, or DKD.

In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD, multiple ASCVD risk factors, or DKD, an SGLT2 inhibitor with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE and/or HF hospitalization. In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or multiple risk factors for ASCVD, a GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE. For many patients, use of either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 receptor agonist to reduce CV risk is appropriate. It is unknown whether use of both classes of drugs will provide an additive CV outcomes benefit. In patients with type 2 diabetes and established HFrEF, an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven benefit in this patient population is recommended to reduce the risk of worsening HF and CV death.

11. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care

CKD

Recommendations

Screening

- 11.1a At least annually, urinary albumin (e.g., spot UACR) and eGFR should be assessed in patients with type 1 diabetes with duration of ≥5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes regardless of treatment. B

- 11.1b Patients with diabetes and urinary albumin >300 mg/g creatinine and/or an eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m 2 should be monitored twice annually to guide therapy. B

Treatment

- 11.2 Optimize glucose control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of CKD. A

- 11.3a For patients with type 2 diabetes and DKD, consider use of an SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with an eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m 2 and urinary albumin >300 mg/g creatinine. A

- 11.3b In patients with type 2 diabetes and DKD, consider use of SGLT2 inhibitors additionally for CV risk reduction when eGFR and urinary albumin creatinine are ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m 2 or >300 mg/g, respectively. A

- 11.3c In patients with CKD who are at increased risk for CV events, use of a GLP-1 receptor agonist reduces renal end points, primarily albuminuria, progression of albuminuria, and CV events (Table 9.1). A

- 11.4 Optimize blood pressure control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of CKD. A

- 11.5 Do not discontinue renin-angiotensin system blockade for minor increases in serum creatinine (<30%) in the absence of volume depletion. A

- 11.6 For people with nondialysis-dependent CKD, dietary protein intake should be ∼0.8 g/kg body weight per day (the recommended daily allowance). A For patients on dialysis, higher levels of dietary protein intake should be considered, since malnutrition is a major problem in some dialysis patients. B

- 11.7 In nonpregnant patients with diabetes and hypertension, either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB is recommended for those with modestly elevated UACR (30–299 mg/g creatinine) B and is strongly recommended for those with UACR ≥300 mg/g creatinine and/or eGFR A

- 11.8 Periodically monitor serum creatinine and potassium levels for the development of increased creatinine or changes in potassium when ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics are used. B

- 11.9 An ACE inhibitor or an ARB is not recommended for the primary prevention of CKD in patients with diabetes who have normal blood pressure, normal UACR (A

- 11.10 Patients should be referred for evaluation by a nephrologist if they have an eGFR A

- 11.11 Promptly refer to a physician experienced in the care of kidney disease for uncertainty about the etiology of kidney disease, difficult management issues, and rapidly progressing kidney disease. A

Epidemiology of Diabetes and CKD

CKD is diagnosed by the persistent presence of elevated urinary albumin excretion (albuminuria), low eGFR, or other manifestations of kidney damage (Figure 11.1). Among people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, the presence of CKD markedly increases CV risk and health care costs.

FIGURE 11.1

Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7." />

Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7." />

Risk of CKD progression, frequency of visits, and referral to nephrology according to glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and albuminuria. The GFR and albuminuria grid depicts the risk of progression, morbidity, and mortality by color, from best to worst (green, yellow, orange, red, dark red). The numbers in the boxes are a guide to the frequency of visits (number of times per year). Green can reflect CKD with normal eGFR and albumin-to-creatinine ratio only in the presence of other markers of kidney damage, such as imaging showing polycystic kidney disease or kidney biopsy abnormalities, with follow-up measurements annually; yellow requires caution and measurements at least once per year; orange requires measurements twice per year; red requires measurements three times per year; and dark red requires measurements four times per year. These are general parameters only, based on expert opinion, and underlying comorbid conditions and disease state as well as the likelihood of impacting a change in management for any individual patient must be taken into account. “Refer” indicates that nephrology services are recommended. *Referring clinicians may wish to discuss with their nephrology service, depending on local arrangements regarding treating or referring. Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7.

FIGURE 11.1

Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7." />

Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7." />

Risk of CKD progression, frequency of visits, and referral to nephrology according to glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and albuminuria. The GFR and albuminuria grid depicts the risk of progression, morbidity, and mortality by color, from best to worst (green, yellow, orange, red, dark red). The numbers in the boxes are a guide to the frequency of visits (number of times per year). Green can reflect CKD with normal eGFR and albumin-to-creatinine ratio only in the presence of other markers of kidney damage, such as imaging showing polycystic kidney disease or kidney biopsy abnormalities, with follow-up measurements annually; yellow requires caution and measurements at least once per year; orange requires measurements twice per year; red requires measurements three times per year; and dark red requires measurements four times per year. These are general parameters only, based on expert opinion, and underlying comorbid conditions and disease state as well as the likelihood of impacting a change in management for any individual patient must be taken into account. “Refer” indicates that nephrology services are recommended. *Referring clinicians may wish to discuss with their nephrology service, depending on local arrangements regarding treating or referring. Reprinted with permission from Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, Greer RC, Choi M, Sequist TD; National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Med 2016;129:153–162.e7.

Selection of Glucose-Lowering Medications for Patients With CKD

For patients with type 2 diabetes and established CKD, special considerations for the selection of glucose-lowering medications include limitations to available medications when eGFR is diminished and a desire to mitigate high risks of CKD progression, CVD, and hypoglycemia. Drug dosing may require modification with eGFR